Stay off Deadman’s Island, the kids were told—which would be repeated many years later when developers wanted to dig on the Nova Scotia island as well

Bill Piers and other kids who grew up in the 1950s along the inlet in Halifax Harbour called the Northwest Arm had heard the stories and the warnings. Stay off Deadman’s Island. Strange lights were seen there at night. The place was haunted, people said, by the ghosts of men buried there long ago.

He figures he was nine, maybe 10, the day he and two friends grabbed shovels and set off to find out if the stories were true. They climbed to the top of a hill crowned with pines and hemlocks and went to work.

“We started to dig and, sure enough, we found some bones,” recalls Piers, now 73. They were sure they were human—and also sure they were in deep trouble. “We were spooked…. One of us said, ‘Oh my God, let’s get out of here. There’ll be ghosts.’” Piers was so scared, he swore never to go back.

The ghosts were imaginary, but the boys may well have disturbed human remains. Deadman’s—as the name suggests— is believed to be the resting place for as many as 400 soldiers, sailors, freed slaves and Irish immigrants.

American connection

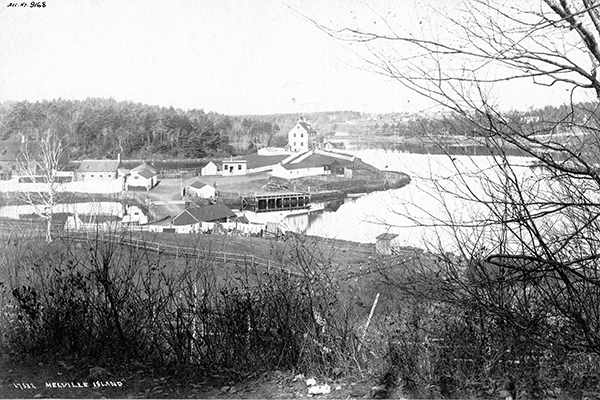

They died of wounds or disease in the early 1800s on adjacent Melville Island, the site of a British military prison during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. The prison was later used as a quarantine station. The warden’s quarters and a stone cellblock survive today as part of the Armdale Yacht Club’s facilities.

It’s the American connection that spared Deadman’s, a prime piece of real estate, from further development. A bronze plaque near the shoreline bears the names of Seth Cleaver, a corporal from Philadelphia, seaman Enoch Gooden, of Newburyport, Maine, and 186 other American prisoners of war, thought to be buried on the island.

“It’s very hallowed ground,” says the US consul general in Halifax, Richard Riley, whose staff organizes a ceremony at the site on the last Monday in May, the day Americans honour their war dead. The annual Memorial Day ceremony, held since 2005, commemorates “not only the American lives lost,” he says, “but the bigger picture of the connection and relationship that we have with our Canadian friends and allies.”

A matter of principle

Yet a place so significant in the history of both countries was almost lost. The island—actually an egg-shape peninsula surrounded by yachts and expensive homes—was slated for a condominium development in the late 1990s, until a community group raised the alarm.

It was “a matter of principle,” says Guy MacLean, a retired history professor and former provincial ombudsman who led the Northwest Arm Heritage Association’s drive to save Deadman’s Island. “You don’t want to disturb sacred ground.”

But is it a lost cemetery? There’s evidence of burials, including a prisoner’s diary for 1814 that refers to Target Hill, as Deadman’s was then known, as “a place where they bury the dead.” And while no archaeological work has been conducted, erosion has exposed bones over the years. In 1959, a decade after Bill Piers’ discovery, Halifax’s Mail-Star ran a photograph of another boy, Ross Bownes, holding a skull unearthed during construction on an adjoining property.

As opposition to the development grew, one of MacLean’s allies—researcher and genealogist Iris Shea—made her own discovery. Copies of British Admiralty records had just arrived at the Nova Scotia archives, and a staff member suggested Shea take a look. The files listed French and American prisoners who had died at Melville prison between 1803 and 1815—names, ages, birthplaces, causes of death—who were likely interred on Deadman’s.

Now a secluded park

“I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, here’s the names of all the people buried there,’” says Shea, who went on to co-author the book Deadman’s: Melville Island and its Burial Ground. Some of the dead of Deadman’s, at least, were no longer anonymous. “The information was exactly what we needed.”

Shea contacted an American researcher she knew, who alerted veterans’ groups and War of 1812 societies south of the border. The battle to save war graves from destruction became big news, even making the pages of the New York Times. With then-mayor Walter Fitzgerald on board, the city bought the island in 2000.

Deadman’s is now a secluded park that doubles as a war memorial. The entrance is just off Purcell’s Cove Road and a ravine trail leads to the shore. Visitors can enjoy the views of the Northwest Arm, or hike up the hill where local boys once dug for bones.

Interpretive panels trace the island’s history and the US Department of Veterans Affairs has inscribed most of Shea’s list of names onto the plaque that honours the Americans who died in Melville prison. “It is important that these men are not forgotten,” says Eric Johnson of the Society of the War of 1812 in the State of Ohio, which has undertaken extensive research to locate victims of the three-year conflict. “It’s all part of closure, so that we know what happened to those people.”

“The men that are buried up there were heroes,” adds Virginia Apyar, president of the Washington-based United States Daughters of 1812. Her group, which represents 5,800 female descendants of Americans who served, erected a monument at the park entrance in 2012 to mark the war’s bicentennial. It not only honours the Americans—”it’s a thank you note to the Canadian people,” she says, “for watching over these guys for all those years.”

Bill Piers, who’s retired after a career selling office equipment, finally returned to Deadman’s 50 years after his boyhood adventure, when he joined the fight to save a site he considers “the jewel of the Halifax area.”

If the condos had been built, construction crews “would have found bones,” he says. “No question whatsoever.” And he should know.