Story and photography by Darcy Rhyno

Dan Conlin ducks down behind a large, fake TV screen, clasps his hands together and casts a shadow onto the screen that looks like a butterfly flapping along. Conlin is a grown man, dressed in a dark blue lab coat. Behind the screen, he’s a boy again, playing at shadow puppetry and laughing at the fun he’s having. He crawls back out from behind the TV screen, dusts himself off and turns back into Dan Conlin, Curator at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 on the Halifax waterfront.

Standing beside a giant lamp draped with sheets that reach to the walls of the room, Conlin says, “In this cool play area, we’re going with the whole blanket fort idea. We built the lamp and TV giant size to make adults feel like kids again.” As proof of this adult-to-child transmogrification, a pair of large shoes stick out from under some couch cushions arranged into a tunnel as if there’s an adult kid playing in there. Conlin sees me checking out the cushion fort. A grin crosses his face. “I’ve crawled through it twice already.”

When he’s not on his hands and knees inside a cozy fort or casting shadow butterflies, Conlin is overseeing a crew of carpenters and designers as they assemble “Family Bonds and Belongings,” an exhibition on loan from the Royal BC Museum. “It’s a colourful, upbeat exhibit,” says Conlin. “It was created with really interesting stories of immigrant families from BC. We’ve adapted it, adding material from our collection to make it bi-coastal.” Family Bonds and Belongings is the museum’s major temporary exhibition in 2019, open to the public from March 9 to November 3.

Gateway to Canada

From 1928 to 1971, a million immigrants passed through Pier 21, known as the gateway to Canada. During World War II, half a million Canadian military personnel departed from this very spot. Today, dozens of cruise ships dock here every year. As a gateway for immigration by sea, and now a National Historic Site, Pier 21 has been compared to New York’s Ellis Island in importance to their respective countries. The Canadian Museum of Immigration opened here on Canada Day, 1999.

“We have a program called ‘The Alumni,’” says Conlin. “If you arrived in Canada at Pier 21, we give you a special tour. We take people up to the landing deck, the actual physical area where the gangways came down from the ships. It’s literally the same doorway where people had their first steps in all of Canada.” This is a poignant moment for visitors. “People often tear up when they remember that experience or what their grandfather told them about finally being on dry land, being in a brand new country, the things they left behind and all the hopes for the future.”

“Immigration is a powerful thread through the history of Canada,” says Conlin. “Unless you’re First Nations, all Canadians connect to immigration in one way or another. It’s fundamental to shaping Canada’s culture and economy in profound ways. It’s a contemporary story that’s still changing the face of Canada today. We like to think Pier 21 is a special place to explore and celebrate that story.”

One of the strengths of the museum is the way it tells chapters in that story. Most are joyous. Many are difficult. Some force Canadians to face our failures. Right in front of the check-in desk in the lobby, a monument called The Wheel of Conscience with four cogs that move, each labeled with a word—xenophobia, anti-Semitism, hatred and racism—recalls the story of the MS St. Louis. The ship with 620 Jewish refugees was turned away in 1939 by Canadian officials who declared that “none is too many.” The ship was forced back to Europe where about 250 of the passengers perished in the Holocaust.

Upstairs in the permanent exhibitions, stories are told of other blatantly racist Canadian policies. To encourage agriculture in the west, Canada encouraged farmers to immigrate, but screened out Black families. In another section, I found it hard to tear myself away from videos of recent immigrants facing racism even today.

Comic relief is necessary when confronting so many difficult stories. In one of the permanent exhibitions, Conlin describes what he says looks like a deli, except all the food is in a garbage can. “We call it the sausage wars,” he says. “The customs folks had restrictions on the kind of food immigrants could bring to Canada. A good natured smuggling war went on between immigrants trying to bring in sausages in pieces and immigration officials trying to seize them. So we built a garbage can, overflowing with seized sausages, cheeses and alcohol.”

Fridge doors and cricket pitches

Conlin continues our tour around the “Family Bonds and Belonging” exhibition. The crew is assembling the 1970s rec room complete with wood paneling and bright orange couches. Here, visitors can relive that period in Canadian family life and watch home movies. There’s also a fridge door, “because that’s how so many families coordinate their day”

To show me how East Coast stories are woven into the exhibition, Conlin shows me a window with a view of a small Nova Scotia farm.

“A Jewish refugee family arrived in 1939—they got out just in time,” says Conlin. “They got to Canada because they qualified as farmers, so this tiny farm in Hants County saved their lives.” The family’s daughter volunteered at the museum up until her death last year. “She gave us her school ID. In the German community where she lived, if you were Jewish, you were forcibly sent to a school where you got this ID with a big ’J’ stamped on it.” Canada got it right in this case, but a chill runs through me at the thought of how a single letter could have sentenced the child to the same fate as those MS St. Louis passengers.

At the centre of the exhibition, glass cases stand in a circle, each displaying a precious piece of clothing. “We have this beautiful Mi’kmaq chief’s coat on loan from the Nova Scotia Museum.”

Coming full circle, we’re back to the giant blanket fort. From living rooms like this where kids turned furniture into toys to cricket pitches like the one in Halifax where teams play other games for grown-ups, this exhibition chronicles the spectrum of human relationships we call families. Home movies, priceless heirlooms, family photos, oral histories, and pillow forts help kids and grownups feel what it’s like to belong to families like theirs and others that look nothing like them. “In putting together this East Coast version of Family Bonds and Belonging, says Conlin, “we’re hoping to create a little bit of magic.”

![]() Header no caption

Header no caption

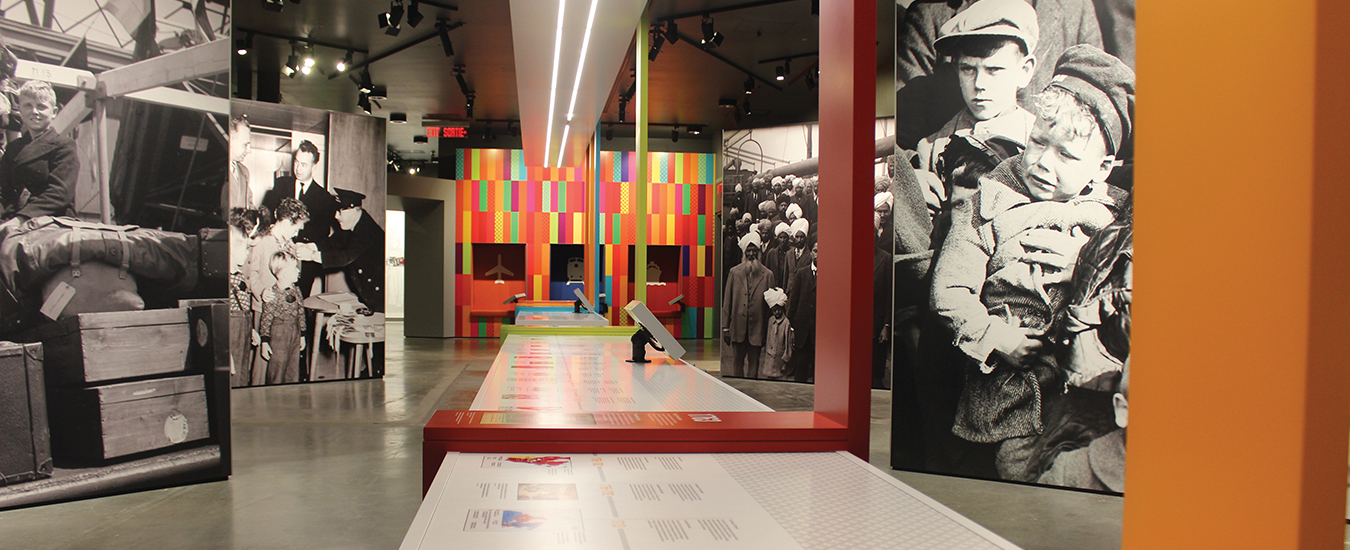

Intro caption: Pier 21 has been compared to New York's Ellis Island in importance to their respective countries.