Back in the ‘50s, neighbours came a-calling every weeknight to get their mail—and to get the local news and gossip

It might be any weekday evening of any year during the 1950s in the village of Sluice Point, Yarmouth County, NS. Around 5:30pm, anyone who was outdoors or near an open window would likely hear the train’s whistle as the train approached the Tusket station, five miles away.

At Abel’s store on the corner, where the men always gathered, drinking Cokes and rolling smokes, someone would say, “There’s the train.”

They knew that in an hour and a half or so, Antoine Babin, the mailman, would arrive in Sluice Point with the mail. On his way down, he would drop off the mail at Abrams River, Hubbards Point and Amirault’s Hill. After our house, he’d continue on to Surette’s Island, the end of the line.

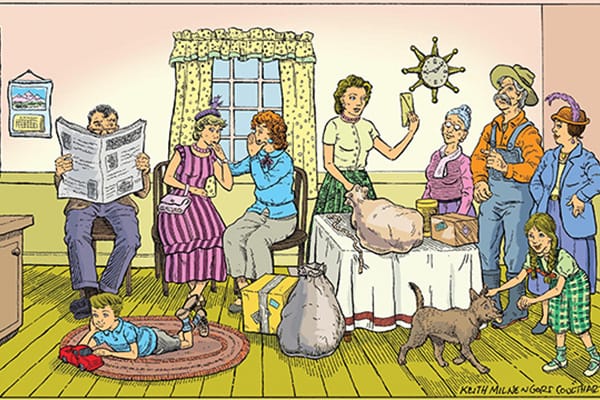

Around 6:30pm, people would start arriving at our house. They’d just walk in—nobody knocked, everyone knew everyone—and take a seat on one of the kitchen chairs, the day bed, or one of the two rocking chairs.

Supper was long since over. The after-supper milking of the cow was done too, the milk resting in shallow pans in the cool stillness of the cellar, its cream slowly rising. Mom might be doing a bit of ironing, or if she was tired, sitting and chatting with the crowd.

There was small talk; gossip. If it was winter, someone might say in the local patois, “Y fait frette, Lillian.” It’s cold. Mom would glance up from her iron. “Est-ce-pas,” she’d say. Ain’t it the truth.

They’d drift in, alone or in pairs. Men, women, children. Some were expecting something in the mail, others looking for a place to go—it was just part of their daily routine.

Someone would ask, “Ton père est-il mieux?” Is your father any better? “Une miette,” might be the answer. A little bit. More details would be exchanged.

“Did you hear about the accident? Young Bobby put his dad’s car in the ditch last night on the curve at P’tit Albert’s. I don’t know what it is with teenagers these days, honest to God.”

General agreement.

Fermez la porte!

The house would fill up some more. Kids who came with their Dad or Mom would play outside the house, sometimes opening the door to ask if they could go to Tommy’s house to see the kittens. “Fermez la porte,” Mom would call out. Close the door. “Yes, yes, go see the kittens,” the parent would say. “Close the door. It’s cold.”

Eventually there would be 10 or 20 people waiting when the truck came crunching into the driveway. Mom would get up. Antoine would come in with a canvas mailbag or two.

He didn’t sidle in; he made an entrance, striding in like a man with a purpose, aware that he had what everyone was waiting for. He’d drop the mailbags on the floor, exchange a pleasantry or two, and turn to leave. Not a chatty man—and I think he took his job seriously. People were waiting for their mail, after all, farther down his route.

Mom would open the mailbags, deftly dump the contents onto the floor, find the packet of letters with the elastic around them, and start giving out the mail, later working her way through newspapers, parcels and so on.

The scene was, for all the world, like those mail-call scenes in war movies. The Sarge has the precious bundle of letters in his fist, and all the soldiers gather around him as he calls out names and hands out letters. “Polanski, O’Neill, MacDonald, Cohen,” he bawls, the men answering, “Here, Sarge.” The names sound like a roll call of surnames from all over the world, but in our case, it was a roll call of Acadian names: “Surette, Bourque, DeViller, Boucher, Corporon,” Mom would call out, often using first names as well, because there were several families to each surname.

There were light bills, family allowance cheques, old age pension cheques, letters from husbands working away or relatives in the States. There were newspapers like the Halifax Chronicle-Herald, the Star Weekly, The Standard, The Yarmouth Light, Le Petit Courrier. Catalogues from Simpson’s, Eaton’s and Dupuis Frères—and mail order parcels from those same three.

If Mom called a name and no one answered, the item was just put aside for a later time when someone from that family would come to get their mail.

Pretty soon, the mail was gone through. Everyone who had showed up had whatever mail belonged to them, and they drifted away. A few might stay to chat a bit. Mostly, the house emptied.

J’peut-il faire?

Of course, there wasn’t just incoming mail. We also took in outgoing letters and parcels. They were weighed, the amount of postage determined; people paid and left. Every afternoon, between 3pm and 4pm, Antoine would pick up a mailbag with our outgoing mail and take it to the Tusket post office, where it was sorted and sent on its way.

When choosing the wall colour, resist the urge to look down at the colour chip in your hand. Holding it at eye level will give you a better representation of what it will look like on the wall. Similarly, the ceiling colour chip should be held above your head to best choose the right colour.

Not all ceilings need to be white; a very pale yellow ceiling will warm up the space. A hint of colour that ties into the wall colour also works. A ceiling painted with semi-gloss will make sure any light hitting the ceiling bounces back into the room.

Once you've chosen your wall colour, paint it in a sheen that has a little more reflective value than you might use in a room with more natural light. Using a pearl finish will help to bounce light around the room. It also has the added bonus of being more washable.

If the basement doesn't have a focal point, solve this by painting one wall a feature colour, and hanging a beautiful piece of art on it.

Screen Placement

Optometrist Leah Gallie says for TV viewing, normal room lighting is best. "When the room is too brightly lit, the screen has less contrast, and when the room is too dark there is too much contrast for comfortable vision."

We kept the “office” part of the post office in the room known as “l’autre bord”—literally, the other side of the wall separating the kitchen from the living room. Back then we didn’t “live’” in the living room; people lived in their kitchens. For us, the room next to the kitchen was the post office.

There was a large wooden pedestal table full of post office stuff, and a built-in cupboard with glass doors and drawers where the official stuff was kept: the registered mail book, the book that sheets of stamps were kept in, monthly report forms, blank money orders.

The cash box was kept in that cupboard too. It was a grey metal box with a handle on top. Easily carried around. Not really heavy-duty, it had a lock with a little key. I’m sure it could have been pried open with a screwdriver, maybe even a nail file. Security was not a big deal in those days.

There were scales for weighing envelopes and parcels, a re-inkable stamp pad and the stamp, which marked all mail leaving our post office. Over the years, we also had a number of devices used to cancel postage stamps. The last one I remember was just like a hammer. It had a wooden handle, a shiny steel shank, and on the end was a small steel cylinder into which, every day, you would insert tiny slugs with letters or numbers on them, forming that day’s date so that you could see on what day a stamp had been cancelled, hence, what day the letter was mailed. This hammer-stamp, about 10 or 12 inches long, was inked by whacking it onto a thick round felt inkpad about five inches in diameter. You then placed the envelope on a rubber pad and whacked the stamps. I was always asking Mom, “J’peut-il faire?” Can I do it? It looked like fun.

Ma place est ruinée!

It wasn’t all fun, however. There was a downside to having people traipsing into your house any time of the day. You had no privacy; your house was open to the public. In the spring and winter, they had muddy boots. And even in the summer, you weren’t immune to floor problems.

One time Mom put new oilcloth down on the kitchen floor. Now, flooring sold off the roll these days is pretty tough stuff, cushiony and long-lasting. But in those days, it was kind of flimsy. Soon after it was laid, a woman from the village came over to wait for the mail sporting a nice new pair of very, very high spike-heeled shoes. Stilettos, really. And it must have been crowded that day, because she didn’t just find a chair, sit and not move. She stood, moved around, and ambled pretty much all over the kitchen. Later that night, the way the light was shining on the floor, Mom could see dozens of little indentations. “Ma place neuve est ruinée,” Mom said over and over. My new floor is ruined. She was heartbroken.

All this for $46 a month.

Ça change tout’l’temps

My parents took over the post office from Dad’s uncle in 1950. When our family moved to Goose Bay, Labrador, in the fall of 1960, the post office was taken over by the wife of Dad’s cousin. We had kept it for 10 years, and then she kept it for another 10 years. In 1970, the Sluice Point post office was closed; after that, folks got their mail in a box at the end of their driveway.

While there had been in the neighbourhood of 35 post offices in the Municipality of Argyle, today there are nine; you might have your mail delivered to you, you might have to pick it up at a community mailbox or a post office—and still, there’s said to be one or two post offices in homes.

Ça change tout’l’temps. Things are always changing.

Rural outmigration, better roads and more cars no doubt played a role in the reduction of postal outlets. In the latter part of the 19th century, people went where their feet could take them, so there was a post office more or less within walking distance of any home, perhaps two miles. But by the 1970s, a car in most driveways meant that people could travel five or 10 miles without feeling inconvenienced.

I remember an ancient fellow known as George à Gervais from the days we kept the post office. I would see him most summer evenings coming around the bend in the road that brought him from his home, smoking his pipe and waving a short branch from a maple sapling around his head to ward off the mosquitoes. Such a low-tech yet practical (and free) solution to the buzzing beasties. Nature posed the problem, but also offered the solution—and it always seemed to me, even as a child, so representative of the simplicity and economy of bygone days.

If I’d told him then that some day the closest post office would be five miles away, in Tusket, he probably would have said that’s a heck of a walk to make every evening.