Angie Cormier’s an ambassador for her adopted homeland and her native tongue

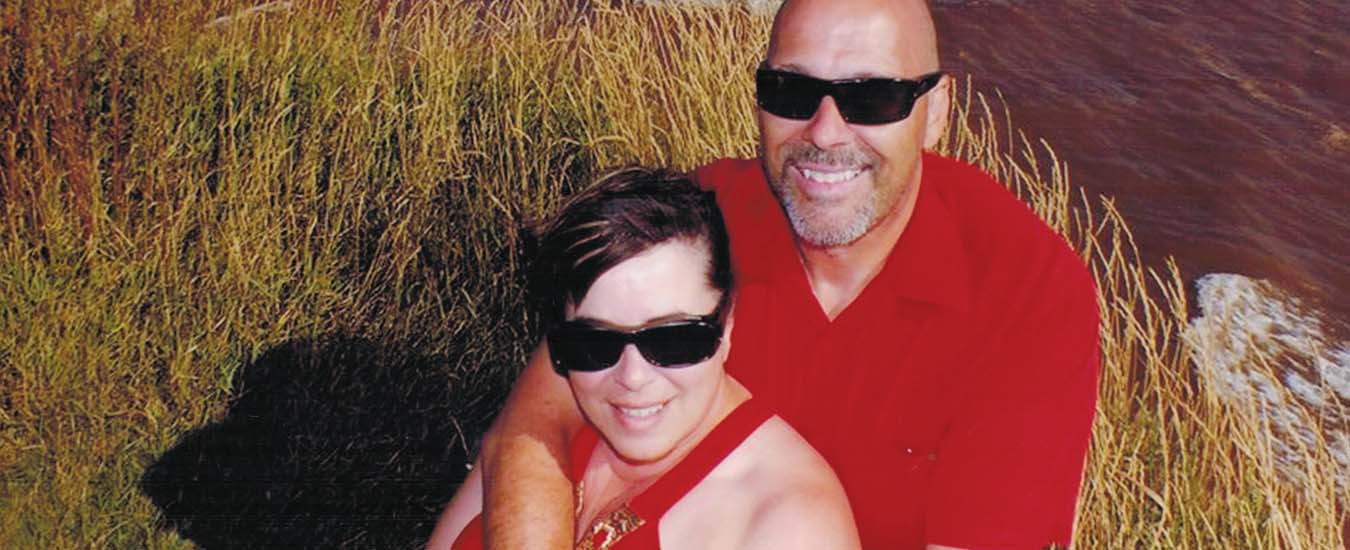

You’d be hard-pressed to find a more enthusiastic booster of Prince Edward Island than Angie Cormier. A self-described “swamp girl,” “princess” and “ragin’ Cajun,” she moved to PEI as a young bride in 1983, knowing nothing at all about the place. Today, as executive director of the non-profit La Coopérative d’intégration francophone de l’île-du-Prince-Édouard, Cormier works to attract francophone immigrants to the Island and help them settle there. She’s also the owner of The Bottle Houses, a quirky tourist attraction featuring houses made from old bottles, in Cape Egmont, where she lives with Aubrey, her husband of 37 years.

A mother of two, Angie was not always a champion of all things Francophone. Born and raised in Louisiana, she comes from a Cajun family, but grew up without speaking French and with no knowledge of her cultural heritage. Today, she is proud of the progress bilingualism has made on PEI, but also worries about the declining number of families who speak French at home.

My great-grandparents didn’t speak a word of English, my grandparents spoke French, and my parents were raised in French, but I wasn’t taught French and didn’t understand it growing up. People of my mother’s generation didn’t want to draw attention to being Cajun. It was more sophisticated to be American. We had a lot of French words mixed in with our English—like for embarrassed, we would say “honte.” “I was so honte.” But I didn’t evenI was born in Jennings, Louisiana. When I was young, I knew my family and my region were different. We were Cajuns. Ragin’ Cajuns. The name “Evangeline” was everywhere: Evangeline Bread, Evangeline Thruway, Evangeline Casino. And our food was different too. When we left our little corner of southwestern Louisiana, people said we were easy to identify, because we were so loud, we cooked good food, and we made music and danced.

know these were French words. I was very ignorant of my history and my heritage.

At university, I did a BA in communications with a minor in French. We were learning a more Parisian French, but the courses sparked my interest. We would have discussions about Cajun French versus French from France. By the end of my four years, I could read and write in French, and I could understand the language, but I didn’t consider myself bilingual. I felt frustrated.

I applied for a scholarship to study French in Canada, and in 1983, I got accepted to go to university in Moncton for a year.

I drove to Canada with a woman who was a TV reporter for Radio-Canada, and who had been travelling in Louisiana. I remember that when we got to Maine, she really wanted to eat seafood chowder. She kept talking about seafood chowder. I had no idea what that was. So, when we got to a restaurant, she ordered chowder and I did too. This white, creamy soup came to the table, and I had never eaten anything like that. My only point of reference was gumbo. Our cuisine was dark, red, spicy, earthy, and I was looking at this bowl of chowder and thinking, “This is what they eat?” I was not impressed at all. I would even say it disgusted me. (Today, I appreciate fresh Maritime seafood and local products, but I still think nothing can compare to Cajun cooking.)

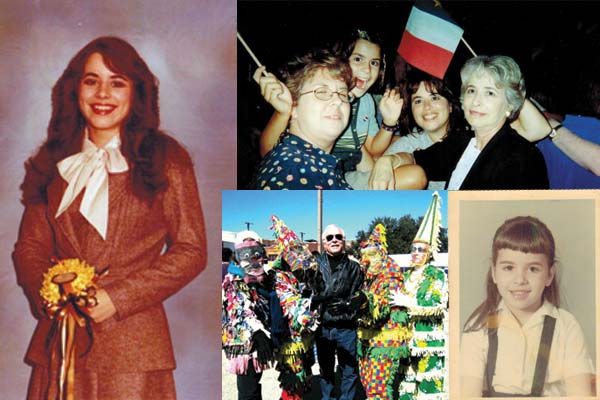

Clockwise from above: Angie as homecoming queen, Kaplan High School, 1980; Celebrating the first Louisiana World Acadian Congress with her mother, daughter and friend in 1999; First grade, Goretti Catholic School, Lake Arthur, LA; “Running the Mardi Gras” with her family in Louisiana, Angie’s favourite time of the year. Courtesy of Angie Cormier.

In Moncton, at the university, I met a Belgian student who lived in residence and told me she made some money working for the campus newspaper, which was called Le Franc. She told me I could probably work for them too, and that I should meet Mr. Cormier, the editor of the magazine. That was Aubrey Cormier, my future husband. I expected him to be older, but he was my age, and he was so handsome. The first time I met him, I fell in love with him. I think he felt the same way, but I didn’t give him much choice! I went to work at the paper, and it was in the old days, when you would literally cut and paste stories onto the page. The problem was that sometimes a story would get cut into pieces and because my French wasn’t good enough, I wouldn’t assemble them in the right order. I had no idea what I was doing.

I left for Louisiana in April, at the end of the semester, with tears in my eyes. Aubrey promised to take the bus and come visit in July. This was in the days before the Internet, so we wrote letters, made cassettes for each other, and ran up very, very expensive phone bills with our long-distance calls.

During one of those conversations, I said, “When you come to Louisiana, we should get married.” I’m the one who proposed. I made all the arrangements, he met my family for the first time, and we got married. Looking back, I think he was very brave. We barely knew each other.

Aubrey only had one condition for getting married: that we would speak French at home and raise our children in French. I said OK. It was a challenge! He had gotten a job on Prince Edward Island, so we were going to go back to Canada and move there. I had no idea where PEI was.

We did nothing to prepare for my arrival in Canada. At the airport, the agent asked the purpose of my visit, and I said I was here with my husband and was moving to Canada. And he told me, “You can’t just come prancing up to the border.” I had to get out of line and go to the interrogation room. They wanted to know what I was really doing here, and I told the agent he couldn’t speak to me that way. My husband told me, “Shh. Stop talking like that. They’re going to have you deported.” Finally, they realized we were just stupid, and they let us go.

So that’s how I arrived in Canada.

We got to Summerside, where we first lived in a small apartment, and I had an immigration agent assigned to me. She would come check up on me and helped with my paperwork. I needed some medical tests, and I had heard there was a card people used at the doctor’s. The first time I arrived at the doctor’s office I took out my credit card, and the poor woman at the reception was horrified. She didn’t know what to do with my credit card, and I didn’t know how I was supposed to pay. Finally, I got to see the doctor and I learned I was pregnant. My mother talked to a doctor back home who told her they had social medicine in Canada and pregnant women were treated like cows on a conveyor belt. I should go back to Louisiana so he could take care of me.

I had a lot of ego. That American attitude. It’s a real shock when you realize the cultural differences. In the South, we were raised like princesses, like dolls. When I was 16 my mother asked me if I wanted to come out at a debutante’s ball. I was the homecoming queen at my school, and I was in parades and pageants. I lasted a year doing that, but I didn’t want to pursue it, even though people encouraged me to participate in pageants.

I’m glad I came to Canada, because I learned a new way to live. One thing that really struck me was that young women and girls didn’t all wear makeup and have their hair done. As a young mother in Summerside, I wound up going to the women’s centre—one of the first in Canada. They were a gang of feminists, and it was a good place for me to be.

I learned a lot about equality between men and women, and it was really a grand awakening for me about the circumstances of women. Coming from the South, it was a whole other culture. I learned about feminism and multiculturalism in ways I had never seen in the States.

I had never seen a woman breastfeed until I got here and met other pregnant women and learned about midwives and breastfeeding. It’s something I had never, ever heard of, and I decided to breastfeed my child. It was the best decision I ever made. I loved it. Loved it. When I went back to Louisiana to visit, and I was breastfeeding, my mother said, “Gross.” She couldn’t believe I was doing that.

We had this old priest, Père Leclerc, and he said as far as he knew, I was the first Cajun to come back and marry an Acadian. He said he wanted to write up my story, but then he passed away. There’s more Canadians going south to good-time Louisiana than Cajuns coming up here. Now, I look at what’s going on in the States, I look back and think, oh my God I am so glad I got married to an Acadian and came here.

When I talk about immigration in my professional role, I really take it to heart, because I know what it was like to be a young immigrant, at a time when we didn’t even really talk about immigration. I was just “from away.” An outsider. I feel a strong attachment to the immigrants who come here and have a lot of room in my heart for them, because I’ve lived through it all myself.