Sheet Harbour pursues its own, unique way on Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore

It was a moment of truth. Through a driving sleet storm in February 2008, scores had come to hear about the future of their little community, shoehorned into the eastern end of the Halifax Regional Municipality. Even then, more than 10 years after Sheet Harbour had been amalgamated into the new HRM, many were uncomfortable thinking of themselves as residents of a big city. What exactly was urban about a place that on a good day was home to 850 people? What was so metropolitan about the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia? For Tom McInnis, though, there were bigger questions at stake.

“I remember like it was yesterday,” says the former Canadian senator, who was born and raised in Sheet Harbour and still lives there at 76, pushing his community’s progress through organizations like the local chamber of commerce, where he serves as president. “It was Groundhog Day and the room where we held the meeting was packed. You couldn’t get near the parking lot. It was incredible.”

For McInnis, and others who had roused themselves for the early morning gathering, the issue wasn’t the recent past, but the near future. He recalls: “How did we want to build this economy here? How could we hold on to our hospital and all our services? You know, the grocery stores, the bank, the service stations?”

In fact, he says, “We’d been going around and around on this in the community for a long time. But at the end of the day, you have to answer the question: ‘What do you want to do with yourself? What are you going to be?’”

“The absorption by HRM had been a mixed blessing. Becoming part of a bigger population centre gave Sheet Harbour representation at the municipal council table where spending decisions are made. But losing its independent stature as a rural community meant that federal and provincial economic and employment development programs and incentives targeted in that direction were harder to come by. Meanwhile, there were still roads and sidewalks to build, and teachers and doctors to hire.”

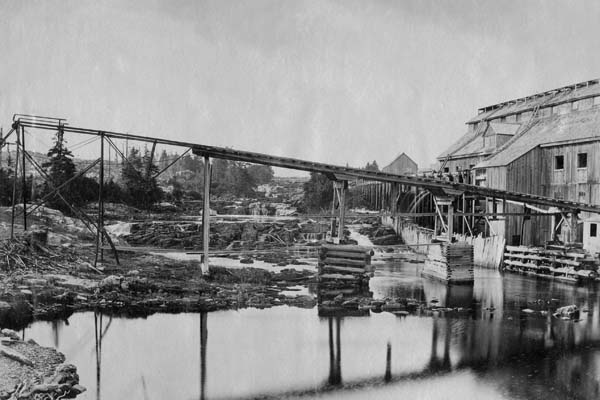

A lumber mill built by Havelock McC. Hart on West River, 1880

All of which had come to a head in 2008. Says McInnis: “We’d hired a group of urban planners from Halifax—Ekistics [now Fathom Studio]—to work on a plan for the waterfront. Now, they were going to present it.” You could, he says, hear a pin drop in the room. “That’s how crucial it was.”

In hindsight, the meeting was important as much for symbolic as pragmatic reasons. The Ekistics document was superbly well-executed—visually arresting and mercifully free of the jargon and preposterous “messaging” to which many plans like it are prone. It focused on the key areas for community development, drawing on existing infrastructure and priorities.

“The history of Sheet Harbour will be interpreted as a foundation for future community growth,” it said. “The scenic beauty of the river and upper lake systems, as well as the unique cultural and natural history will become a must-see destination for HRM residents and tourists, while becoming a source of pride for the community. The quality of the improvements will create jobs and will anchor Sheet Harbour’s position as a true destination in the Province of Nova Scotia.”

Some of those improvements would include things people can touch: street scaping, boardwalks, upgrades to historic properties, and new recreational facilities.

But others, maybe the most important ones, were about what people could imagine their community becoming: neither strictly metropolitan, nor technically rustic; not less than either but somehow more than the sum of both parts; a unique destination of choice for visitors and new residents alike, a stone’s throw (albeit with an enormously strong arm and tiny pebble) from the urban jungle and the rural wilderness.

Since that meeting, Sheet Harbour has been pursuing its own, third way with something close to missionary zeal. At McInnis’s reappointment as chamber president in March, he reacquainted the crowd with the marching orders they’d been following for a dozen years and bid them to, in effect, don’t stop thinking about the future.

“I have long had a deep and serious interest in that for this area,” he said. “Gone are the days of having government handout projects. None of this is easy but now the community decides what we develop and what we are going to do.”

He said: “We will revisit projects we have been developing and I’ll ask the chamber’s directors to work with me for further development. The list includes: an amphitheatre; Heritage Memorial Park; provincial park in [nearby] Moser River; walkway and lighting of the [downtown] West River Falls; town square at MacPhee House [museum]; bringing MacPhee House Museum back to what it was; waterfront development; and trails association for trails through the woods from bridge to bridge.”

What’s more, and significantly, he said: “We have newcomers who are building or purchasing homes, who are consumers…bringing children to our school population—and who are using the essential services…. We need to attract people to the area and to keep them in this area.”

The moment of truth had come full circle. Now, the question was: What will the next 10 years be like for a place named for a flat rock at the entrance of its harbour, just down the coast from the biggest city in Atlantic Canada?

History books chronicle nothing outstanding about Sheet Harbour’s European settlement in the late 18th century. Like many communities up and down the Eastern Shore, it was peopled by Loyalist refugees and British veterans of the American Civil War. In the 30 years between 1837 and 1897, the record of the community’s major developments reads like a laundry list from an imperial surveyor’s log book: New church built (1837); another church built (1860); sawmill built (1863); new schools built (1867); Freemason’s hall built (1869); another school built (1870); post office opened (1873); bridge built (1889); yet another school built (1897).

Sheet Harbour didn’t get economically interesting, it’s fair to say, until Halifax Wood Fibre Company built the first sulphide pulp mill in Canada along its East River in 1885. (It shut down six years later when the price of sulphide shot up). Then followed a ground-wood pulp mill, owned by the American Pulp and Wrapping Paper Co. of Albany, NY, in 1922, on the West River. (That stayed afloat, under successive owners, until 1971 when Hurricane Beth blew it down).

Since then, the lobster fishery has been a steady employer. Schools and the Eastern Shore Memorial Hospital provide jobs, as do many small businesses and entrepreneurial enterprises up and down this stretch of Nova Scotia Provincial Highway 7. There’s also Sheet Harbour Industrial Port, built in the 1990s and operated by the Halifax Port Authority. It currently ships wood chips for the pulp industry and imports wind turbine segments, which are then transported across Nova Scotia and to the rest of North America.

But really, the place isn’t…well…known for much of anything else. Not “Nova Scotia known,” at any rate. Not like Lunenburg with its shipbuilding and sea shanties. Not like Cape Breton with its Bras d’Or Lake and Alexander Graham Bell.

Of course, that depends on who you talk to. If you talk to Janice Christie, for one, you get a different impression. She’s a correspondent for the Guysborough Journal (full disclosure: so am I) who covers the area. Born and raised in the area, and now 65, she’s lived and worked here all her life. “I have a broad perspective of the community,” she says. “The community that I live in is really the Eastern Shore, which is made up of so many little communities.”

Sheet Harbour’s identity is tied up with places like East Ship Harbour and Ecum Secum Bridge, she says. “Back in the day when I was a kid, each of those little places were thriving with their own churches, and schools. Every time there was a government announcement, people would think it was about

a big industry arriving, which never really came to fruition. But over the past few years, communities have been surviving and growing, if not thriving, because of that personal tenacity that you see in the broad community along the Eastern Shore.”

That tenacity reached a zenith most recently when despite some of the leanest times for public spending in recent memory, Halifax Regional Municipality allocated $3 million from its hard-working capital budget for a new recreation centre in Sheet Harbour—for the community, an unprecedented 21,000 square-foot, multi-use facility incorporating a fitness complex, meeting hall and library. That was in May 2020. Five months later, the federal and provincial, governments joined the party with a combined $6.5 million in grants towards the Eastern Shore Lifestyle Centre.

To Tom McInnis, the timing could not have been better. “Increasingly, we have a real challenge attracting and holding professionals here,” he said at the time. “Doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, teachers…. It’s difficult, being kind of an outport area. You have to have things for them to do. Our old centre just can’t do the job anymore. This is a good project, and it’s required now.”

But what made this project less of a handout and more of a hand-up was the enormous amount of planning at the local level, a process that effectively began as long ago as that fateful meeting in 2008, when Fathom outlined, from its consultations with the community, a vision for a new community. A centre as a social and economic catalyst—and not as just a place for arts and crafts and pick-up games of basketball—may not have been on the agenda that day. But it, or something like it, was there in spirit, bound to happen.

Says McInnis today: “You have to dream, and you have to work towards the dream. Otherwise, there’s no enthusiasm

to get it done. It’s not a matter of building something, and others will come. They will, and that’s great. But we’ve got to buy into this locally. We have to have the dream that we will do this for ourselves.”

Certainly, for people in their 20s and 30s here—folks who don’t want to fall into the time-honoured Maritime habit of leaving home and going up the road in search of opportunities—driving local success with local ideas is not merely a good idea; it’s a matter of personal, professional and community survival. For them, negotiating that liminal head space between rural culture and urban sensibilities is a fact of daily life here. And dreams are the nurseries of hope.

“I thrive off of growth and improvements, and I just see so much potential for Sheet Harbour as part of the whole Eastern Shore right now,” says Rebecca Atkinson, who was raised here by parents she describes as entrepreneurial. She, herself, is the founder and proprietor of Sober Island Brewing, a craft brewing operation she started in 2015 when, on a trip to Cardiff, Wales, she fell for a particular Oyster Stout and decided Nova Scotia needed one to call its own. Since then, she and her handful of employees have grown the enterprise from a 50-litre (about 80 cans) to an 800-litre system. Not even COVID-19 has managed to derail her progress.

“It’s really about attitude,” she says. “I love the people and the quality of life I have here in Sheet Harbour, but sometimes there’s still this attitude that whatever we have here just isn’t quite good enough. But, when you are really invested in that community’s future growth, it just leads to greatness for everyone.”