When the great opera diva, Joan Sutherland, was asked the secret of her success, she is said to have replied, "bloody hard work." Artists who achieve greatness or notoriety do so by refining raw talent in the furnaces of effort and perseverance. Nova Scotia artist Bruce John Wood is no exception to the rule.

A native of Truro, NS, Bruce had no family models or outside mentors to whom he could turn for guidance in how best to channel his creative urge. He didn't come from a long line of known artists. There was no one to send him to an expensive school or to apprentice him. His mother (who, according to Bruce, "could draw a little") was an employee in the Stanfield's underwear factory. His father worked for a plastering contractor and as a janitor. None of Bruce's siblings-five sisters and one brother-showed any particular interest in or aptitude for art.

Bruce, on the other hand, had talent. He was also driven. An inexplicable inner force challenged him to create. "It's something that has been with me all my life," he reflects. "As long as I can remember, I wanted to be a painter and a sculptor." Even in his primary grades at Willow Street Elementary School in Truro, and later at Central High School, Bruce was the one who would be called to the front when the teacher wanted the blackboard decorated for Christmas or for some other special occasion. This suited him fine. His ability to draw gave him a measure of prestige among his peers, a scarce commodity for a smallish lad who was shy and not much inclined towards competitive sports.

In fact, Bruce wasn't fond of school at all. He completed Grade 9 and, at the age of 16, headed "down the road," first to Toronto and then through much of the United States, and on to the West. In Winnipeg he took a 10-month welding course at the Manitoba Institute of Technology. He spent most of his shop time creating metal sculptures that had little to do with his teacher's instructions. This lack of attention to curriculum assignments won him few marks in the course. Bruce did notice, however, that the instructor held onto most of what he had created. It didn't bother him. "It was a time for youthful adventure, for exploring and for seeing the world beyond the Maritimes."

At the age of 21 Bruce returned to Nova Scotia, attended trade school in Cape Breton and became a licensed oil burner mechanic. He married and settled down to the business of providing for a family that soon included two sons. For the next 20 years he worked at his trade for Wilson's Fuel and as an independent mechanic.

"It was a living, but it was killing me spiritually," he says. "I felt eaten up. I did what men were traditionally taught to do. I worked at a job in order to provide for myself and for my family. But always there was this urge to paint and to sculpt." There is restrained emotion in his voice as he speaks. "I felt guilty if I didn't paint. Then again, I felt guilty when I did, because when I found time to take up the brush, the message I heard was, 'What are you wasting your time at that for?' It was a catch-22 situation."

When the boys had grown, Bruce and his wife parted. Bruce abandoned the oil burner business and opened a small gallery on Willow Street. He called it "Academy B," in recognition of one of his great idols, Sandro Botticelli. Bruce carefully studied the works of Botticelli and other great masters: Rembrandt, da Vinci, van Gogh, Degas, Michelangelo. More recent figures, like Paul Peel, a 19th century Canadian whose attention to detail had a profound effect on many Canadian artists, also influenced his style.

Reading and study may have provided inspiration and given him a grasp of essential technical knowledge, but his greatest learning came by practice. He would pick up a chunk of wood and carve almost anything: a mermaid on a rock, an old salt on a barrel, a miniature schooner, or a salmon. "Sometimes I would take an old bottle and torch it into an interesting shape and sell it," he explains. "Back then I could get all of $5 or $10 for small items sold through a local gift shop on Willow Street."

Bruce gradually moved to larger wood sculptures. Never content to settle at any stage of development, he progressed from wood carving to creating bronze casts, teaching himself every step of the way. Often the process was one of trial and error, but his mastery of technique and the use of various media evolved and grew.

Bruce has learned, for example, the "lost wax process" for creating a bronze cast sculpture so thoroughly that he dismisses its complexity. "It's a tried and proven method dating back at least to the Ming Dynasty," he says offhandedly. Just the same, the one-and-a-half times life-size, red fox he recently shipped for casting at a foundry outside Toronto took several months of painstaking creation. It faithfully captures the essence of a living fox. And it will fetch him a commission at least a thousand times what he once got for his small sculptures at the gift shop.

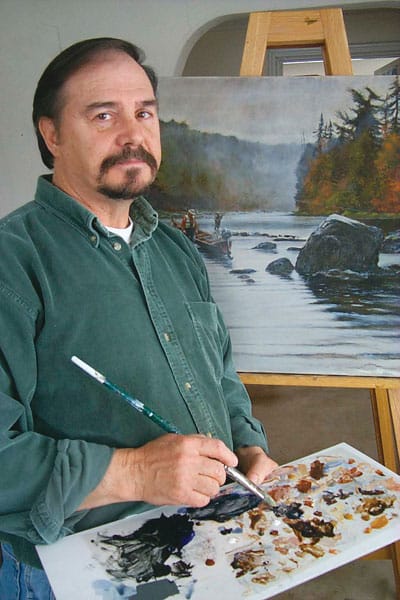

In the 18 years since Bruce Wood decided to devote himself full time to art, his work has evolved. He has become a master sculptor, painter and illustrator. His oil paintings of idyllic salmon pools, boats at rest, or awe-inspiring wilderness scenes, are a balm to the soul of anyone who loves the Canadian outdoors. They have been reproduced as covers and illustrations in outdoor magazines like Eastern Woods and Waters, Ducks Unlimited, and The Atlantic Salmon Journal. His limited edition wildlife prints, such as The Mysterious Eastern Cougar, The Elusive Marten, or Ducks of the Woods, have enjoyed wide acclaim. Government departments have commissioned him to produce paintings and posters. He has illustrated three Canadian books and has painted at least four massive wall murals for the Town of Truro. His prints, paintings and sculptures have found homes in corporate and private collections nationally and internationally, and he has been honoured with recognition and awards too numerous to list.

Like painters, sculptors and artists throughout the ages, Bruce wrestles constantly with the dynamic tension created by the practical need to turn out what he calls "commercial" work on the one hand, and his spiritual drive to create the ultimate masterpiece on the other. He works well under the pressure of a deadline, but will not release a carving, a sculpture, or a painting until he is satisfied with it. "You have to please yourself first," he says.

Art is the pursuit of the ideal. Still, Bruce realistically admits, "You have to know when to let go. I don't stockpile my art. It's created to be sold and when it's gone I don't yearn after it. Somewhere out there it has a life of its own, its own set of relationships with those who view it and care for it. And I find that gratifying."

Bruce Wood may have been a fine oil burner technician. But those who know his paintings and sculptures are happy he gave it up a long time ago.