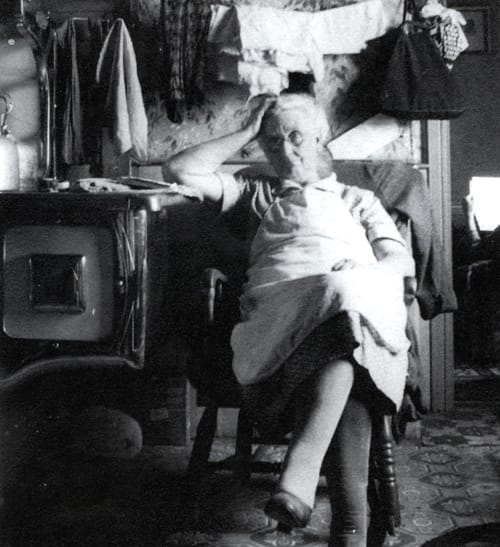

"I wouldn't want to live in 'them times' again, but the memories are precious" ~ elderly Island woman, 1991

It was such a long time ago that I can't tell you when I began collecting old, black and white photos of Prince Edward Island…

My partner, Andrea, and I have a small acreage in Ft. Augustus, PEI. One day we had just finished shingling the back side of the little chicken coop, and as I was walking up to the house, I stopped to survey all the additions we had made to the place over the years-the horse barn, the fences, the stone wall and even the raspberry patch. It's just a small property on a back road, but a place where we get to make the decisions, and where the results of our work are evident. As I continued on to the house I got to thinking about the rural culture of my childhood, and how the Island was covered with similar small places, where people could see all around them the signature of their own industry. They didn't have much money or control much of the world, but they were masters and mistresses of their own domains. At that moment I felt a strange solidarity with all those disappeared rural Islanders who, from time to time, looked up from their work and felt pride in what they had accomplished.

In the mid-1900s there were approximately 10,000 family farms scattered across the Island-typically a house, barn and sundry outbuildings on a strip of cleared land, with a bit of a woodlot at the back-the average size being slightly more than 100 acres. They were almost all involved in mixed livestock and crop farming. While few generated more than a subsistence, they represented a long tradition of rural intelligence and aptitude, promoting feelings of competency, even mastery, and providing a source of identity and pride.

Island families and communities were tremendously self-sufficient, and when folk rose in the morning or retired in the evening, it was with the sense that the society they inhabited was largely the result of their own labour and ingenuity. There was an immense dignity in that self-reliance, but it came at a steep price; one revealed in the calloused hands, weathered faces and weary, sloping postures of many who appear in the old photographs. If the way of life was determined largely by the tough physical exigencies of wresting a living from the land, it was also affected by the delicate social art of living all your life under the daily scrutiny of family members and close neighbours. The hard work, the frugality, the self-sufficiency, the reticence, the conservatism, the stubbornness, the ready hospitality, the deferential piety and prickly pride were all qualities rooted in the farm experience; qualities that have become the hallmarks of Island character.

There were also, of course, many fishing families on the Island, but they too were a rural lot, and few of them survived just by fishing. Like their neighbours they were also tillers of the soil and keepers of domestic animals. What makes these photographs especially evocative is that they portray a largely vanished world. The hundreds of anonymous men and women who actually took the pictures with their Brownie Box or Folding Pocket cameras didn't realize they were documenting the final years of a pre-industrial rural order-what occurred in PEI during the middle of the 20th century was nothing short of an agrarian revolution. By the 1960s it was becoming more and more clear that the backbone of the society-the small, mixed family farm-was no longer viable within an increasingly mechanized and consumer-driven economy. One after another, hundreds of Island farmers surrendered quietly and grimly to the big machinery and bulk tanks. There were those who prospered from the change, but most just gave up. By the end of the century, approximately eight out of every 10 farms had ceased operating, and many rural communities were without a single resident farmer.

Small farms were not the only casualties of the great program of change, with its catchwords of consolidation, centralization and rationalization. The one-room schoolhouse, the local general store, the village garage and many other less visible elements of the old rural order began to disappear. For good or ill, all manner of old patterns and identities withered as increased mobility, the mass media, economies of scale and technological innovation combined to transform the structure and narrative of Island society. The new age of convenience and consumption had arrived late, but it had arrived, sparkling with novelty and colour.

The old black and white era was laid to rest, but after the wake we still had our memories, our stories and our old photographs.

Someone said to me that the camera doesn't lie. They were, of course, wrong. The world of "them times" viewed through the camera lens is certainly less difficult and less layered than the world our parents and grandparents actually experienced. There is an inescapably sentimental aspect to most picture-taking, which predetermines what we are able to see. This was even more a factor during the early 1900s in PEI-many photographs of the time were snapped by visiting relatives (mainly from New England) looking for nostalgic souvenirs.

As I think back over the process of collecting these photographs one memory in particular stands out. In home after home as I prepared to open the albums set on the table before me, my typically unassuming Island hosts would say, "There's probably nothing here you would be interested in." As you see, such was seldom the case.

Excerpted from Pride in Small Places: A Photographic Remembrance of Rural Prince Edward Island 1900-1960, by David Weale; published by Tangle Lane, Charlottetown (2004). David Weale is a folk historian who lives in Ft. Augustus, PEI.