A blizzard like this comes along, oh, once every hundred years or so, and is talked about for years… until the next big one.

It started innocently enough, with no indication of what was to follow. The morning had been mild, with snow melting on rooftops and streets. It even seemed that rain could be a possibility. Then late in the afternoon the air became noticeably colder and snow began to fall. It continued to fall lightly all evening, and by midnight became heavy. It soon became obvious that this was no ordinary snowstorm.

The snow carried on all night, accompanied by high winds that blew it into huge drifts, many more than seven feet high. People awoke the next morning greeted by snow banked against windows and doors, with streets impassable to all but the hardiest of folk. "Blizzard Strikes Province and Suspends All Business in City and Country" blared one of the newspaper headlines of the day. It was the same story from one end of Nova Scotia to the other, as well as in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

White Juan? No, this was 100 years ago, almost to the day, when another momentous snowstorm hit the area.

Snow had been falling for more than a week, but by Wednesday, February 15, it looked as if conditions might improve. However the snowfall that afternoon and evening, combined with the plummeting temperatures and high winds overnight, soon destroyed everyone's hopes. The Great Storm of 1905 was in full swing.

The single most devastating result of the storm was the obstruction of the railroads. At the time, the vast majority of goods, including essential supplies of food and coal, were moved by train; roads were still largely unpaved and virtually blocked in winter. During the brief mild spell snow banks had prevented melted snow from running off, and it then froze, encasing the rails in "a solid mass of ice which can only be removed by the thaws of spring or the pick-axes of many hundreds of men." In many places the ice was several inches deep underneath new snow drifts.

Citizens along the railway running into Nova Scotia's Annapolis Valley were asked to go out and help clear the lines. Even the churches appealed for volunteers. A statement issued by Wolfville's mayor, Dr. G.E. DeWitt, was read from the town's pulpits, urging anyone who could to go to work, "pay or no pay," clearing the snow and ice off the tracks in order to "save themselves and open up communications." DeWitt telephoned his fellow mayors in Kentville and Windsor, imploring them to ask their citizens to do the same.

On Monday, February 20, the Halifax Herald noted, "An appeal like this is unprecedented, but so is a winter like this. No one ever heard of anything of the kind before in Nova Scotia and it is certain that no such conditions ever existed." The mainland railways were either stopped completely or running only a few trains, while "the small railways in Cape Breton are tied up as completely as if they had never been built," leaving the island in "splendid isolation."

Other parts of the Maritimes fared similarly. On PEI, matters were "no better than on the mainland," with more than 500 men at work constantly trying to clear the lines over the past two weeks. Two trains near Hunter River took a week to progress five miles and the whole island, from Souris and Georgetown to Tignish, was described as "one immense cutting, at places from 20 to 25 feet deep."

In Moncton, some coal got through from mines at Springhill and elsewhere over the weekend, narrowly averting a "fuel famine" and saving the city's gas and electric lighting plant. Only the dumping of a car of coal by railway authorities narrowly averted a disaster at St. Joseph's College in Memramcook, NB, where "there was barely enough coal on hand to run the heating and lighting plant through Saturday."

Just over a week after the first storm, on Thursday, February 23, a second snowstorm hit the region, making all the efforts of the past few days fruitless. Ships were prevented from leaving the port of Saint John and snow quickly drifted into rail cuttings so labouriously just cleared by hand.

Food began to run out, especially flour. It was reported that, "In parts of Cape Breton the people are living from hand to mouth, while in the lumber camps and on the farms, feed is short, so short that horses have had to be shot and cattle killed."

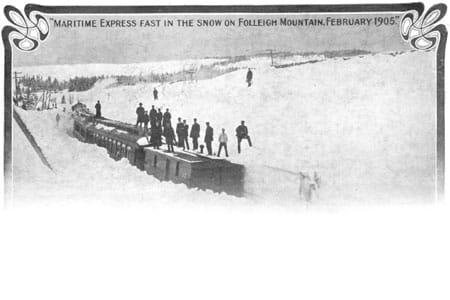

At Folleigh Mountain (now Folly Mountain) in Nova Scotia's storm-fraught Wentworth Valley region, the No. 34 Maritime Express went off the rails on Friday and was soon completely buried in drifting snow. An initial rescue attempt failed "because of the snow, drifted there by a fierce north-easter that raged all day with hail so biting that men could not work." The train was freed four days later, with men shovelling snow up embankments 30 feet high.

After more than three weeks of battling what newspapers called the "Storm King," the snow blockade began to be lifted for good on Monday, February 27. The Great Storm of 1905 became the one that everyone talked about for years to come, setting the yardstick against which all others were measured.

At least until the next big one struck.