He's an artist, not an "artiste." He works with silver, but he's no silversmith. He is part Inuit, but sometimes, he isn't Inuit enough. He refers to himself as a fabricator, a maker of things. To his family, he is honest, straightforward, easy-going, down-to-earth, the eternal jokester. To the eldest of his three children, Keshia (a shy 10-year-old), he is a "very cool" role model. He is Labrador-born, now Kippens resident, Michael Massie. You can call him Mike, or Michael, depending on how you say it.

In a region characterized by ice-bound, snow-covered, raw natural glory, Michael Massie was a city boy. Happy Valley, population 8,655, is a military town, home to the Goose Bay airbase and oft-controversial yet highly lucrative low-level test flying. Its populace is young, ethnically diverse, well-educated and moderately wealthy. Massie is a product of the area's eclectic mix of residents. His mother's parents are Inuit. His paternal grandmother is part Inuit, part Naskapi. His grandfather on his father's side is Scottish. Despite the strong dose of aboriginal blood, Michael, 37, was raised as a Kalunak (the Inuit word for white man). As a child he was an avid doodler who enthusiastically duplicated, from cover to cover, "Little Devil" comic books. He says it was exciting growing up in Labrador and, in spite of his urban upbringing, his favourite memories centre around family gatherings "out on the land." His grandfather, a hunter and trapper, taught him how to work a trap line. "It was a good experience," he says simply as he recalls the family reunions his Inuit relatives held every two years. "We did a lot of camping in the summertime at Mulligan (Lake Melville) where mom grew up. I knew more people there than in Goose Bay."

Although emotionally rooted in the land and traditions of his ancestors, Michael the artist has long outgrown his home town. In 1981, the 19-year-old travelled to St. John's where he completed a commercial art course, discovering it wasn't really what he wanted to do. He returned to Happy Valley, but 1986 saw him in Stephenville, taking a two-year visual arts course. It was there, he says, that he learned to draw. It was also where he met his future wife, Jo-Ann Ryan. He was a student, she worked in a store. "It's one of those stories," she says. "I loved him before we met." She explains that she would see him coming into the store and that she just knew there was something special about him. After "confiding" her interest to a friend (one who she knew would pass the word on!), she and Michael got together. "I liked him, he liked me. It was a mutual attraction. It was as simple and as complex as that."

After Stephenville, it was back to Labrador for six months and then on to Halifax where Michael enrolled at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. There, he experimented with painting and print-making, but he says it didn't click with him. Nor did he click with some of the instructors. "I hated to be told what to do. I can't stand authority." In his third of eight semesters, he finally found his niche. "I had a friend who was doing jewelry.

I liked the mechanical stuff, seeing how little things worked, the smell, the materials. Right away, I was hooked."

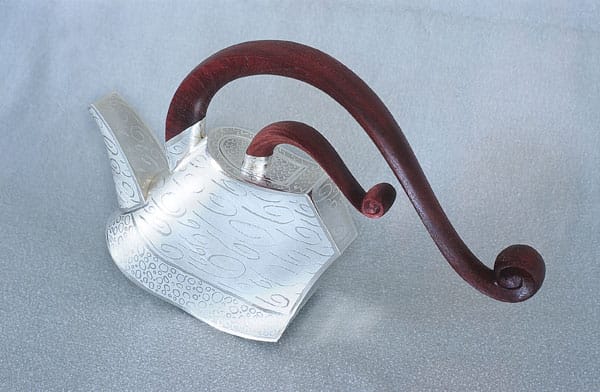

Part of his course dealt with silversmithing and one of his assignments was to create a hollow vessel in silver. It was around this time that his maternal grandmother died. Michael says he remembers her always drinking tea. Even at her funeral, as the family sat around reminiscing, everyone was drinking tea. He decided to make a teapot for his class project, dedicated to his grandmother.

It is an image that continues to show up in his work. To date, he has made and sold 39 teapots (ranging from $2,000 to $4,000) and four complete teasets including the teapot, tray, spoon, sugar and creamer (fetching prices between $8,000 and $14,000). All are unique works of art, each carefully handcrafted in silver and intricately designed. These wondrous representations of objects found in everyday life have become, through Michael Massie's act of creation, treasured objets d'art. Most are sold through the prestigious New York gallery, Alaska on Madison, and some through a Vancouver-based gallery, Spirit Wrestler, which specializes in aboriginal art. Private collectors snap up the rest. "Yes," he acknowledges, "my work tends to be geared towards the people with big bucks. I never intended that, the price tag just grew out of the cost of the materials I use."

Now, he wants to try something new. Again turning to his Inuit heritage, he talks of the legend of Sedna, the Inuit sea goddess whose story he has been researching. "It's fascinating," he says in his softly melodic, slightly exotic accent. "There are many variations of this story. In the one I'm using, there is a tale about an orphaned young girl, back when girls were considered less important than boys because they didn't hunt. She was taken to an island and left behind to die. When she saw the boat leaving without her, she swam out and tried to climb in the boat. Her grandfather cut off her fingers until she fell off the boat. That is when she became Sedna. Her fingers became the creatures of the sea and she controls them. When people abuse things, when they don't share their food with each other, then Sedna gets upset and she holds back the creatures and people get hungry. Legend has it that the shaman would have to comb her hair because she was still just a little girl who liked having her hair combed. When he combed her hair, she would relax and the animals would be free so the people could eat again." Michael is re-creating the legend as a moving sculpture more than eight feet across, composed of wooden carvings of fish, seal and walrus. At opposing ends of the mobile will be Sedna and the shaman, gracefully suspended in their perpetual chase, never meeting.

Now, he wants to try something new. Again turning to his Inuit heritage, he talks of the legend of Sedna, the Inuit sea goddess whose story he has been researching. "It's fascinating," he says in his softly melodic, slightly exotic accent. "There are many variations of this story. In the one I'm using, there is a tale about an orphaned young girl, back when girls were considered less important than boys because they didn't hunt. She was taken to an island and left behind to die. When she saw the boat leaving without her, she swam out and tried to climb in the boat. Her grandfather cut off her fingers until she fell off the boat. That is when she became Sedna. Her fingers became the creatures of the sea and she controls them. When people abuse things, when they don't share their food with each other, then Sedna gets upset and she holds back the creatures and people get hungry. Legend has it that the shaman would have to comb her hair because she was still just a little girl who liked having her hair combed. When he combed her hair, she would relax and the animals would be free so the people could eat again." Michael is re-creating the legend as a moving sculpture more than eight feet across, composed of wooden carvings of fish, seal and walrus. At opposing ends of the mobile will be Sedna and the shaman, gracefully suspended in their perpetual chase, never meeting.

Michael explains that his work allows him to explore his Inuit culture and express it on his own terms. One of his early pieces was a silver ulu bowl. An ulu is a crescent shaped knife with a T-shaped handle in the centre of the blade. The instrument was traditionally used by Inuit women for domestic tasks such as cleansing skins or cutting meat. His creation consisted of a silver bowl resting on a stand of three ulu. The bowl represents the kudlik, or Inuit bowl used for heating and light. It is needed to sustain life. For Michael, the ulu bowl showed how he felt about becoming a father and how the addition of daughter Keshia created a family. "I saw the three of us as working together to sustain life, all of us supporting each other."

Describing art in this way makes Michael uncomfortable. "Halifax (i.e. the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) was intellectual, with everyone explaining why they did something a certain way. What baloney! Art is supposed to be fun and playful and good to look at. Art is freedom of expression. If you enjoy it, why can't that be enough? Why does it have to be something more? Why does it have to be based on a theme?" He describes how, during one of his classes, someone brought in what looked like a Nazi symbol, three pieces of I.V. tubing held together with duct tape. "That person had 16 pages to explain that thing. I didn't think it was art. I think people who do too much art like that drink too much caffeine."

People who quibble over details, who get caught up in what he considers minutiae, are the bane of Michael Massie's existence. Although much of his art is a reflection of his aboriginal heritage, there are those who complain that he isn't really Inuit. And, despite having been featured on the cover of Inuit Art Quarterly, some critics say Michael's work isn't really Inuit art. They say he's just a white man using Inuit images. Michael shrugs off the naysayers, explaining that such attitudes are nothing new to his family. His grandparents, the Scottish grandfather and Inuit/Naskapi grandmother, experienced the same prejudice. When he hears the comments that he isn't Inuit enough, he says it helps him better understand what his grandparents must have lived through. "Anyway," he says, "times are changing and I find that people today are more interested in liking other people for who they are, not what they are." As for the debate over whether or not his work fits in the pure cultural genre of Inuit art, Michael really doesn't care. "As long as I'm getting something out of it, I'm happy. I prefer to satisfy myself rather than worry about everyone else. They either like it, or they don't. It's as simple as that."