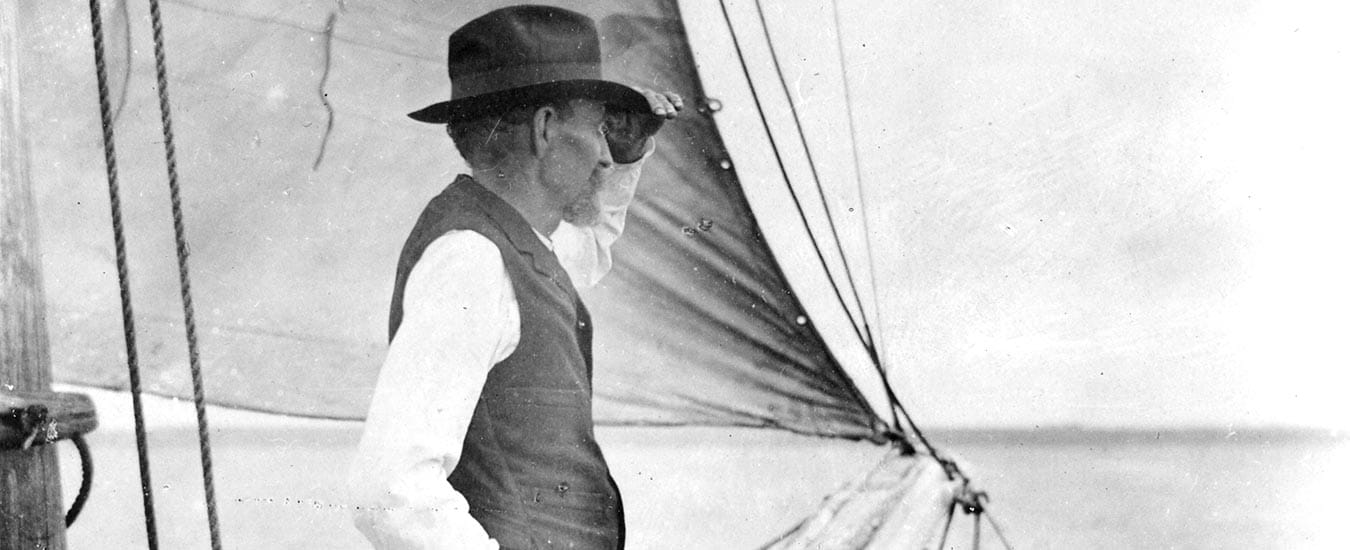

With no money and no job prospects, Nova Scotia-born mariner Joshua Slocum set off to sail around the world and became one of history’s greatest adventurers

ON FEBRUARY 11, 1896, Joshua Slocum steered his wooden sailboat into the Strait of Magellan, a blustery stretch of water that links the Atlantic and Pacific oceans near the tip of South America.

A Nova Scotia-born captain from Brier Island, Slocum was alone in a 36-foot sloop as he encountered whirlpools, strong winds, brisk currents and marauding locals seeking to plunder his vessel. At one point, a ferocious storm hit his small boat, stripping the sloop of its sails.

“I saw now only the gleaming crests of the waves. They showed white teeth while the sloop balanced over them,” Slocum wrote of the experience in his classic account of the journey, Sailing Alone Around the World. “No ship in the world could have stood up against so violent a gale.”

The conditions were so rough that Slocum, despite three decades of experience at sea, became seasick. “This was the greatest sea adventure of my life,” he concluded. “God knows how my vessel escaped.”

Though many Canadians haven’t even heard of him, Slocum is arguably history’s greatest sailor, ranking among the world’s top adventurers such as Sir Edmund Hillary (who, with Tenzing Norgay, was the first to summit Everest), Ernest Shackleton (known for his adventures in Antarctica), and undersea explorer Jacques Cousteau.

Slocum’s round-the-world voyage in the late 1890s was the culmination of a life spent at sea, and one that propelled the sailor to fame and into the record books as the first person to sail around the world alone.

From boot shop to sailing ships

In the years leading up to his journey, Slocum had risen up the nautical ranks to become a master mariner. He married a woman who shared his adventurous spirit, raised four children at sea, and became a well-to-do captain, commanding ocean-going tall ships that sailed the world over, from New York to Japan.

Slocum’s life started off humbly. He was born in Mount Hanley, NS, where he lived until age eight, when his family moved to Brier Island. There Slocum endured a hard childhood; he was pulled from school at age 10 and forced to work in his father’s boot shop. At 16, following the death of his mother, young Slocum took to sea for good.

As a young seaman, Slocum proved himself hard working and intelligent, quickly mastering celestial navigation and working his way up the ranks from ordinary seaman to first mate. He sailed around Australia and visited ports throughout Asia.

By 1869, Slocum, then 25, was the captain of the Montana, a San Francisco-based schooner. His commands increased in responsibility and prestige, and a year later, he was bound again for Australia aboard the Constitution. There the young captain met Virginia Walker, an adventurous American-born young woman well suited to life as a captain’s wife. (One of the couple’s children recalled their mother shooting sharks from the stern of their ship with a Smith & Wesson revolver.)

Slocum’s career as an ocean-going captain peaked at age 37 with a post as captain and part-owner of the Northern Light, a grand vessel that boasted three towering masts and three decks. He called it his best command. “I had a right to be proud of her, for at that time—in the 1880s—she was the finest American sailing-vessel afloat.”

By the 1890s, however, Slocum’s situation had deteriorated. After being hammered by a series of setbacks—including shipwreck, the death of Virginia at age 34 and mutinies, including one that forced him to shoot and kill a member of his crew—Slocum found himself unemployed and in debt. Author Clifton Johnson concluded in a 1902 profile of Slocum: “Misfortune dogged his heels and nearly every venture he made, whether on land or sea, turned out a dismal failure.”

Around the world

By 1892, Slocum was 48 and like many captains at the end of the Age of Sail, he found himself an aging man in a fading industry. His money was gone, his prestige was diminished and his skills were no longer in demand.

In addition to being a talented sailor and navigator, Slocum was also a skilled boat builder. With his employment options bleak, he set out to restore a derelict sailboat given to him by an old acquaintance. Working in Fairhaven, Mass., on the shore of the Acushnet River, Slocum spent $553.62—and 13 months—rebuilding the 36-foot sloop, the Spray.

In the years following the Spray’s relaunch, Slocum spent some time fishing aboard his new vessel. But he was no fisherman. He was a sailor. So, with little else to do and just $1.50 to his name, he hatched a plan: he would sail around the world alone.

On April 24, 1895, Slocum hauled up the Spray’s anchor and sailed out of Boston Harbor. “A thrilling pulse beat high in me. My step was light on deck in the crisp air,” he later wrote. “I felt that there could be no turning back.”

One of the captain’s first stops on his solo voyage was in his childhood home of Westport on Brier Island. “To find myself among old schoolmates now was charming,” he wrote. “The very stones on [Brier] Island I was glad to see again, and I knew them all. The little shop round the corner, which for thirty-five years I had not seen, was the same, except that it looked a deal smaller. It wore the same shingles—I was sure of it.”

Slocum later evaded pirates off Gibraltar; nearly drowned after running aground on a beach in Uruguay; and gave public lectures about his travels in ports from Australia to South Africa. An avid reader, he also stopped at locations of literary significance, including Samoa, where he met Fanny Stevenson, the recent widow of author Robert Louis Stevenson, one his literary idols.

On June 27, 1898, Slocum guided the Spray into Newport, RI, thus ending a ground-breaking voyage that covered 46,000 miles (or 74,000 kilometres) and spanned more than three years.

Today, countless people hop in GPS-equipped boats with all the modern conveniences—from refrigerators to laptops—and sail the world’s oceans.

For a full month Slocum sailed across the Pacific with no other guide than the heavens above. “The Southern Cross I saw every night abeam. The sun every morning came up astern; every evening it went down ahead. I wished for no other compass to guide me, for these were true,” he wrote.

Slocum had grit, courage, ambition, and a lifetime of nautical experience in his favour. Yet he was not without flaws or dark chapters in his life.

In May 1906, less than a decade after his famous voyage, Slocum was arrested and charged with raping a 12-year-old girl. He spent 42 days in jail before accepting a lesser charge of indecent assault. (The alleged incident was eventually downgraded to a “great indiscretion.”)

Slocum had a thin skin and a short temper and was at times a very distant father and husband. During his round-the-world trip, his family often had no idea where he was. His second wife thought he was dead for a stretch of the voyage. He simply didn’t write his family many letters.

In 1908 (many reports claim it was 1909, including the memorial plaque on Brier Island), he disappeared after setting out aboard the Spray from Martha’s Vineyard, telling friends in New England (his home later in life) he was heading to South America. He was never seen again.

Legacy worth remembering

On Brier Island, many reminders of Slocum’s life remain. The cobbler shop where he fashioned leather boots under his father’s watch remains on the edge of Westport Harbour. Today it is a heritage property, painted bright red.

Down the road from the shop is a monument honouring Slocum. Unveiled on July 22, 1961, it consists of a bronze plaque affixed atop a cairn made of beach stones. When I visited, the plaque was tarnished and dirtied by seagull droppings, and the cairn was worn and cracking—almost symbolic in its neglect.

Even though Slocum’s story might be faded, his legacy is still felt by those who fully appreciate the significance of his adventures—sailors like him.

On a hill above the Westport waterfront is a cemetery. There a weathered headstone marks the resting place of Slocum’s mother, Sarah. On the day I visited, a small glass spice jar rested at the foot of the headstone. Rolled up inside was a damp, ink-stained note signed by five captains, including one building a replica of Slocum’s famous sloop. It read: “Thanks for having a son that has inspired thousands to take up tools to rebuild or build boats from scratch. And to fulfill their dreams of far away lands...”

For Slocum, the sea offered a place of peace and refuge, despite the danger.

“To face the elements is, to be sure, no light matter when the sea is in its grandest mood,” he wrote. “But where, after all, would be the poetry of the sea were there no wild waves?”

Quentin Casey is author of Joshua Slocum: The Captain who Sailed Around the World (Nimbus).