On a late September day in 2023, I meet Chief Hugh Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik and Fundy Baykeeper, Matthew Abbott, at a small memorial park on the banks of the Skutik (St. Croix) River overlooking the Milltown Power Generating Station.

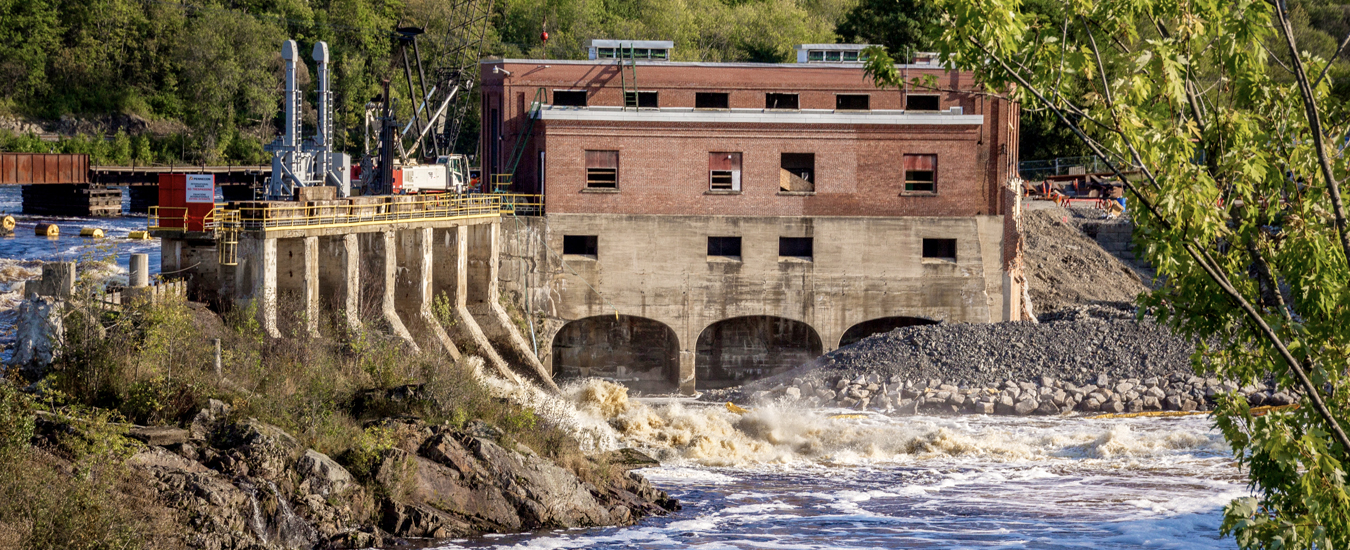

Far below, a channel of water on the opposite shore thunders past the station housing one of the oldest hydro dams in Canada and rushes over a rock outcropping, cascading in a creamy froth to the river below. The rest of the river’s width remains hidden behind sections that NB Power began decommissioning in July. In another month, the station would also be gone.

Abbott breaks the silence. “A decade ago,” he says, “we could not have dreamed of this.”

Back then, Abbott was participating in a 130-kilometre relay run from Sipayik (Point Pleasant, Maine) to Forest City, N.B., a route that follows the spawning migration of the Siqonomeq (known as alewife, river herring, or gaspereau), a small fish indigenous to the river system. At that time, 98 per cent of its prime spawning habitat was inaccessible to the alewife due to multiple dams and obstructions. The population, having plummeted to 16,000 fish from over 2.6 million in 1987, was in crisis.

The relay was an act of awareness and a cry of protest.

“There’s a long tradition of sacred runs with the Wabanaki,” says Abbott, referring to the alliance of First Nations of the northeast: the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq, and Wolastoqey.

In May 2023, they held another relay. This time, the mood had shifted. The alewife no longer had to navigate the Milltown fishway. The first of many artificial barriers on their northbound migration from ocean to river spawning grounds was gone.

“It was super emotional,” says Abbott. “I was running with some of my heroes. You know things are going well when something starts as a protest and ends as a celebration.”

Chief Akagi points to the channel where water surges past the generating station. “We call this the Salmon Falls. That’s where the fish ladder was. It allowed salmon and other fish passage up the falls and past the dam.”

The soft-spoken chief said ladder removal was the first stage in decommissioning the dam and restoring approximately 16 kilometres of river, five million square metres of spawning habitat, in the Skutik. When complete, the full width will be open again.

“We are specific to our river,” Akagi says. “This river is what defines me.” He watches the current froth over rock. “People forget what we really had here.”

The People

Before retiring from the Sipayik Environmental Department in Maine, Ed Bassett was one of the earliest voices advocating for river restoration.

“What happened to the river and the fish is a metaphor,” says Bassett. “A living metaphor for what has happened to the Passamaquoddy. By law, the fish have been blocked or banned from spawning in their native habitat to almost the point of extinction, and for native people, that’s also a pretty common story.”

The traditional home of the Passamaquoddy (called Peskotomuhkati on the Canadian side) once encompassed 16,257 square kilometres between the watersheds of the Penobscot River in Maine, and the Wolastoq (Saint John) River in New Brunswick. The Skutik watershed was the beating heart of this territory, providing the tribe with physical, cultural, and spiritual sustenance.

“Our homeland,” wrote Bassett in a report documenting his nation’s relationship to the river and the alewife, “offered the Passamaquoddy a rich and diverse environment … pristine woodlands, fertile valleys, mountains, island, fresh water lakes, rivers, saltwater estuaries, and the ocean with incredible tides offering limitless supplies of food twice a day.”

The Passamaquoddy, which means People of the Pollock (a marine species once plentiful in the region), enjoyed a deep connection with both inland and marine environments. They easily travelled the waters of the river and bay in birch bark canoes. An ancient fishing village known as Siquoniw Utenehsis existed at the Salmon Falls. The people converged there each spring to harvest the sea-run fish.

When the pollock ran close to shore, Bassett wrote, “Many community members would come down to the beach and wade into the water and simply grab the large Pollock by the hand or with a pitchfork and then fill everyone’s baskets.”

They also fashioned fishing nets and weirs to capture the migrations of alewife and salmon. The diverse harvest provided fresh food, while smoking preserved nutrition for the winter months.

“This region was known as a nursery ground for whales and porpoises, its own unique ecosystem that you wouldn’t find anywhere else in the world,” Bassett says. “A Fundy oasis; an oasis in decline. No wonder the Passamaquoddy wanted to live here. It was a garden of Eden.”

His people lived in companionship with the river for more than 13,000 years.

Then, in 1604, Samuel de Champlain and his crew sailed into the mouth of the river. They spent only one ill-fated winter on a small island, but it signified change. Europeans had arrived. Soon, buildings and roads were built atop ancestral homes and burial grounds. The settlers began exploiting the natural resources, constructing a cotton mill and tannery, industrial sawmills, pulp mills, and dams along the river. In 1798, United States and Canada delineated themselves, settling on the river as a boundary. By then, the Passamaquoddy had also been split up and displaced; most on reservations in Maine, and others spread throughout their territory in New Brunswick. The river that bound them, now separated them.

The People of the Pollock suffered, and the Skutik suffered. The alewife began to disappear, and all that depended upon it.

“That balance had been there for thousands of years,” says Bassett. “And in a matter of 300 to 400 years, it was totally destroyed.”

A river runs through it

On an isolated patch of bog in central New Brunswick, the Skutik River begins as an unremarkable creek flowing into Mud Lake, then continues a twisted path 185 kilometres southward through the Chiputneticook Lakes before emptying into the Bay of Fundy.

With the spread of colonial settlements, rather than being valued for its natural beauty, abundance of wildlife, and food, the Skutik became valued as an energy source for industry and a receptacle for effluent from tanneries, sawmills, and pulp and paper mills. Dams diluted the pollution from the mills. Meanwhile, loggers stripped the forests, and logs scoured the river bottom as they flushed downstream, upsetting the river habitat. After the alewife and other sea-run fish populations, including Atlantic salmon, crashed in the 1800s, fishways were constructed to allow passage around the dams. Gradually the alewife rebounded, and at some point, smallmouth bass appeared.

Over time, camps sprouted along the lakes and outfitters began catering to recreational fishermen. In 1995, they successfully lobbied Maine to close two fishways on the American side, blocking the alewife spawning habitat upstream.

“The outfitters placed high value on the smallmouth bass fishery and feared large numbers of native fish, like the alewife, would outcompete the bass, which are non-native,” explains Abbott. “The people along the lakes seemed to have no generational memory of the alewife (being present), but the Peskotomuhkati memory dates back thousands of years.”

By 2002, the fishway at the Milltown Dam recorded only 900 returning fish, undermining both the freshwater ecosystem of the river, and the marine ecosystem of the Bay of Fundy. As a fatty, high-nutrient fish, and a keystone species, the alewife is critical to both, serving as feedstock for puffins, eagles, bears, raccoons, cod, haddock, seals, and whales. Like the Atlantic salmon, alewives hatch in fresh water, then migrate to the ocean where they spend three to five years as a saltwater fish before returning to their natal rivers to repeat the cycle.

“If we want to get the salmon back, then we need the alewife,” says Abbott. “They’re a food source and a cover for the salmon. If you have 10 million alewife, a lot less salmon get picked off by predators.”

Removing barriers

Soon, the plight of the alewife became politically charged. It seemed everyone had a stake in the future of the fish: conservation organizations, grassroots environmental groups, fish and game associations, guiding associations, Indigenous nations, residents, politicians, and government departments at all levels in two countries.

Chief Akagi and Bassett helped found the Schoodic Riverkeepers, a grassroots group of volunteers who worked alongside tribal governance to investigate the importance of alewife to the ecosystem, with their cultural connection as guidance. They soon realized that the Skutik was the most significant producer of alewife on the eastern seaboard. By restoring the river and the alewife, they would positively impact animals all the way up the food chain to humans.

“The Schoodic Riverkeepers did some powerful work,” says Abbott. “They made a video and went community to community to build the support for restoration. Building unity and understanding within the nation was critical, then they could speak with one voice on both sides of the border.”

In April 2013, Maine passed state legislation allowing the Woodland and Grand Falls dams to be reopened. Numbers of returning fish quickly rebounded.

Over the subsequent years, the Riverkeepers and their partners travelled every kilometre of the river, developing a comprehensive restoration plan, and building highly skilled teams to carry out restoration activities.

In 2020, the various governments, stakeholders, and tribes finally signed a statement agreeing to cooperate to restore the river system.

“That was my biggest moment,” says Bassett. “This was a teamwork effort, in which countless people were involved. I was happy to be part of it.”

That a small fish brought together so many with differing agendas and interests was indeed remarkable. But then something happened that no one expected.

NB Power came up with a plan to install a new, high-tech fishway at the Milltown power dam and contacted Chief Akagi as part of the consultation process.

“Consultation really means they tell us what they’re going to do,” he deadpans. “Honestly, I took one look and said this can’t be real. Imagine an auger in the middle of the river passing the fish up and down. It was a meat grinder!” Chief Akagi, who had retired after a lengthy career as an estuary ecologist with the federal government, proposed that removing the dam would be more economical. “It was dated, and only generated three megawatts of power, which went to the States,” he says. “It was a windmill. They were blocking our river for a windmill.”

NB Power crunched the numbers and agreed to remove the dam.

The world that was

Chief Akagi shares a memory from his childhood of walking the beach in front of his home with his father and a very tall family friend. A salmon washed ashore and the friend picked it up by the gills and slung it over his shoulder.

“The thing I always remembered was that salmon’s tail dragging on the ground. That had to be a six-foot (two-metre) fish.” He pauses, looks to the river. “That was natural, that was in this river, and that’s the fish my people used to live off. People don’t believe such stories, but that’s the world that was here.”